The Code of Justinian: At the Source of Our Criminal Law and Legal Reasoning

The Code of Justinian is our main source for understanding Roman law. This collection of legal texts was published on April 7, 529, more than fifty years after the fall of Rome (476), by Justinian, the Eastern Roman Emperor (with the capital at Constantinople), as part of his effort to restore the political greatness of Roman civilization.

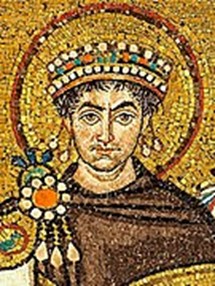

Justinian, Eastern Roman Emperor

Justinian, Eastern Roman Emperor

Justinian (482-565) had been reigning since 527 and was seeking to reconquer the territories lost by Rome, considering himself its representative and heir. To this end, he launched military campaigns in Spain, North Africa, and Italy against the so-called barbarian peoples who had driven out the Romans. However, military conquest alone cannot suffice to restore Rome's prestige, and renewal, if it is to last, must be based on strong political power founded on law.

Roman law, until then, was certainly fixed in writing, but its sources were scatte-red, sometimes even contradictory. Justinian entrusted the jurist Tribonian with the mission of assembling a commission of experts tasked with codifying Roman law. In legal terminology, the verb «to codify» means «to construct according to a coherent system.»

Justinian's code is therefore primarily a construction or reconstruction, baseo on scattered materials, of a coherent Roman law applicable to all citizens of the empire.

The Code of Justinian

The Code consists of three parts: The Constitutions, the Digest, and the Institutes, to which are added the laws promulgated by Justinian himself after 534.

The Constitutions form a collection of decrees and laws promulgated by the emperors who preceded Justinian. The Digest constitutes a more challenging part, composed of commentaries and points of legal doctrine by Roman jurists.

The Institutes, on the other hand, are a kind of legal and procedural manual intended for students.

Book IX of the Constitutions is dedicated to criminal law.

The measures taken by the emperors appear extremely severe by today's standards. Punishments ranged from exile to an island to death by the sword, with forced labor in mines in between. Torture was institutionalized in procedures, especially in cases of defamation, false accusations, and treason.

Nevertheless, some measures aimed at regulating abuses seem relevant today: no one could be detained beyond the duration of their sentence, inspections were organized with provincial governors to monitor the exercise of their judicial power. Justinian also reduced the use of mutilations, thereby prohibiting the cutting off of both hands and feet of criminals, and forbidding its application to thieves.

Other measures, however, seem absurd to us today, bordering on the ridiculous. For example, those sentericed to the mines, one of the most severe forms of forced labor, were to be tattooed on their arms or legs to make the reason for their conviction visible, but not on their faces, which «were designed to reflect the beauty of paradise.» This mention of paradise reflects a progressive Christianization of Roman law.

Thus, Justinian's Code could be reconciled, in the Middle Ages, with Christian doctrines, to form the basis of legal education in the earliest universities of Europe, such as Bologna or Padua.

Our University possesses a copy of the Digest, dating back to 1612 and printed in Savoy by Stéphane Gamonet. Such a late printing of this classic proves that French jurists were still drawing inspiration from Roman law long after the end of the Middle Ages.

Ecrit par la BU Vauban